|

home |

|

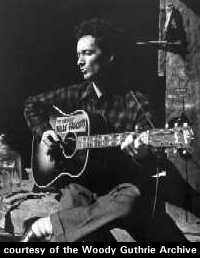

Rebound for Glory: More Thoughts on Woody

When I last had a hero, I was eight years old. My world revolved around climbing trees, hiding Playboys from Sister Katherine Anne, and taking my first guitar lessons. My hero was Yaz. No, not the new wave band of "Upstairs at Eric's" fame, but Red Sox great Carl Yastrzemski. He was my hero because I liked baseball, he was famous, and my uncle gave me a poster that Yaz signed. Now I'm older, married, and more critical of famous people. I don't have Playboys to hide and most tree-climbing experiments end badly. I still play the guitar, though I have progressed only a few chords. But I finally have a new hero. Woodrow Wilson Guthrie was born in Okemah, Oklahoma, on July 14, 1912, named for that year's Democratic presidential nominee. Woody was a folksinger, hobo, sign-painter, philosophizer, union booster, merchant marine, writer, father, husband (a few times over), and radio personality. He squeezed more life into his 55 years than most writers dare to fictionalize. I think about heroes often. Every year, the last assignment I give to my College Writing One students at the University of San Francisco is to explore heroes, their evolution in our lives, and the role of the media in forming, and ruining, our heroes. Heroes, my students and I have decided, can be flawed. Woody Guthrie was as flawed as they come.

Woody was, by most standards, a terrible husband. He went through three wives and he left them often to hit the road or the rails; reported his whereabouts rarely; cheated on them and didn't hide it; and had children with all three. His financial support, too, was unreliable, although well-intentioned. He was also a drinker whose benders sometimes led to outrageous scenes, fights, and arrests. But while Woody abstained a little less than other heroes my students come up with every year (Mother Theresa, say), he was equally good to his fellow human. He gave away almost everything he earned to his wives or to unions or to those down on their luck. In the late 1930s, Guthrie sent out small mimeographed songbooks to radio listeners who requested the words to his song that, according to Pete Seeger, contained the following at the bottom of the page:

And he channeled his passions and talents into causes both social and political, from the pre-Stalin Communist party to farm workers of California. Woody devoted his life to seeing and helping this country. In fact, Woody Guthrie was a patriot. I must say, it's hard for me to call my hero a patriot. From the Trail of Tears to the Reagan years, there's a lot of shit that went down in the name of patriotism that keeps me from flying the old Stars and Stripes in front of my home. But Woody was a patriot in the good sense of the word: he loved this country and thus tried to change it, mostly through song. Take, for example, the often-ignored fourth verse of his most famous song, "This Land is Your Land," and tell me this guy is not a patriot Sarah Vowell would approve of. If heroic status necessitates a tragic demise, Woody obliged with a slow, awkward decline due to Huntington's disease, a genetic degenerative illness that ravages the mind and body equally. Tragic as it may be, some of the more poignant aspects of Woody's life stem from this disease. Woody spent the last fifteen years of his life in Brooklyn State Hospital lonely, unable to write much or think clearly or control his twitches. At the end of a late letter to his second wife Marjorie, Woody wrote: Pilgrims and visitors included Marjorie, old friend Pete Seeger, the widow of folksinger Leadbelly, and young songwriter Bob Dylan. In 1967, Woody heard a recording of son Arlo's first hit, "Alice's Restaurant." The echoes of Woody's work abound. Where Woody wrote simply about bankers robbing farmers, Arlo sang of being dragged down to the station for being a litterbug. Straightforward critiques of police, politicians, bankers, and businessmen ring throughout the music and lyrics of both father and son. Woody died on October 3, 1967. Thirty-four years after his death, Woody is finally in vogue, it seems. Billy Bragg and Wilco have recently set dozens of his lyrics to music. The Smithsonian traveling tour of Woody's art, original lyrics, and life continues until 2002. A biography by Joe Klein has recently been reissued in a trade paperback edition. And the latest Woody tribute album includes the likes of Bruce Springsteen, Ani DiFranco, and the Indigo Girls. And it's about time. Woody inspires me to be idealistic, humble, generous, and silly. I have been picking up the guitar more often. I calmed a screaming two-year old recently with my improvised three-chord masterpiece "Sometimes the Moon Comes up." Baseballs players fall to cocaine and domestic violence, Schwartzkoff's battles were a little muddier than George Washington's, and, c'mon, politicians? Mother Theresa was obviously a powerful force for good, but could I go out for a beer with her? So where do you look for hope? Consider Bob Dylan's answer in "Last Thoughts on Woody Guthrie:"

Pete Mulvihill runs Green Apple Books, a landmark bookstore in San Francisco, and teaches expository writing at the University of San Francisco.

| click on image to view larger photo | |||||||||||||||||||||||